On the Ythan at Logie Buchan

(Chris McElvar photos)

Photo courtesy of Ellon Castle Gardens

from pre-Pict to post-Trump

To Begin at the Beginning

Ellon might have been just another market town, but for the strategic importance of its location. It occupies the site where the River Ythan is shallow enough to be forded and this ford was, until recent times, the main crossing point on the coast of what is now Aberdeenshire for goods and people passing between the Buchan and Aberdeen areas.

The surrounding countryside is mostly crops and grazing, hardly surprising given the fertile land created by the rich, alluvial deposits on both sides of the river. The most obvious physical features, apart from the large boulders deposited by retreating glaciers are the low, gently undulating hills and woodland – excellent walking and cycling country.

But before the people came the land. Ellon rests on a platform of mainly volcanic and metamorphic rock. Back then, the Ythan was a big river. Rising in the Bisset Hills, it crossed the ice sheets and emptied into the Norwegian trench when the British Isles and Europe were one. As our most recent Ice Age ended, a new sea emerged and the Ythan was curtailed where it now meets the North Sea between the dunes at Newburgh Beach and the Sands of Forvie. 10,000 years ago, this warming climate brought Stone-Age peoples, with their religions, arts and farming, to the British Isles from Southern Europe and the Mediterranean regions. Much of the evidence of these migrations has been lost to the sea – as the ice sheets retreated, sea levels rose to swallow the remains of early settlements. Yet we know they existed: fishermen still dredge up stone implements and weapons in shallower waters and excavations in the Sands of Forvie suggest that the Ythan Valley has been settled continuously since before 5,000 BC.

At Ellon, islands had formed in the Ythan, prompting the widely held belief that Ellon’s name began with the Gaelic “Eilean”, meaning “island”. In the 12th century Book of Deer, Ellon was Helan. It has been Elin, Helin, Elan and Elon, all of which are similar enough to come from that same Gaelic root. As for the Ythan itself, it has been the Aithan and the Ethin, both close enough to “athan”, a Gaelic word meaning “ford”. The Ythan is home now to water fowl and otters, trout and salmon, anglers and the occasional canoeist. Its tributaries and estuary have provided settlers with all manner of shellfish for millennia. Indeed, excavations around the estuary provide evidence of the large scale processing of shellfish for export, not just to feed the locals.

Along the Ythan valleys, archaeologists have identified cairns, stone circles and cists, many destroyed or badly damaged in previous centuries by farmers and builders before their importance was understood. Most standing stones suffered a similar fate, but one of these “menhirs”, the Candle Stone, persists at Drumwhindle. On the Hill of Logie, about a mile downstream from Ellon, evidence of round, stone-built huts from the Iron Age is clearly visible. And further downstream near the estuary, a village from that same period has been unearthed (unsanded?) at Forvie. A stone circle of unknown purpose stood on the riverbank near Aldi’s current location at the charmingly named Pinkie Park. The 3ft high stones are still visible upstream on the riverbank, though sadly not in the original circle. And if you visit the Prop of Ythsie, take a look at the stone circle known as Druid Temple, started around 3000 years ago, when the third phase of Stonehenge was under constructon.

The Iron Age

Ancient urns, flint and granite axes, scrapers and weapons from all over the area have found their way to museums in Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Glasgow and beyond. There is evidence of a Roman camp at Auchinhove near Keith and, back in Ellon, we now know that there was a small settlement near the Ythan ford as early as the 3rd century BC.

In the British Isles, most advances in governance, administration and technology have, until recent centuries, originated in the tribes and nations settled around the Mediterranean and spread from there. The Iron Age was no exception. It seems to have arrived in Buchan around the 3rd century BC, a thousand years after it began.

What did the Romans ever do for us?

Not much, to be honest. In the 1st century AD, Roman governor Julius Agricola crossed the ford at Ellon with legions intent on subduing the Northern tribes. The tribes in the low lying and fertile parts of the north eastern coast formed part of a group known to the Romans as the Taexali (thanks to a single mention by historian and geographer Ptolemy, who accompanied Agricola). Little is known about this group of tribes. The people lived in small, undefended farms and hamlets and made religious offerings of fine metal objects, a practice which differentiated them from the neighbouring Caledonii and Venconi. Taexali settlements and rituals differed greatly from those of the Highlands and Islands. Potential conquerors had a major problem in the North East in such times: there was no one in overall charge who could surrender. Population was sparse, the closest thing they could find to a king was a local chieftain or head of a successful family, and small-scale guerrilla warfare was the order of the day. The Taexali didn't do pitched battles. A large army could march for weeks, meet very little opposition, lose some scouts and advance parties in the process and not control anything worthwhile by the end of it.

In the early 3rd century, Agricola was probably followed by the Libyan-born Emperor Septimius Severus at the head of around 40,000 troops. You’ll come across a lot of “probably” and “possibly” in any histories of the region before the 9th century AD but we know that Severus and his dangerous heir, Caracalla, made it from the Tay to the Moray Firth by sticking to a coastal route. There is little evidence of interaction with the Romans and the ailing Emperor decided to call it a day, claiming victory over a handful of chieftains and heading to York to die.

The Picts

The Picts were most likely a mix of the indigenous tribes that resisted the Romans (such as the Taexali and the Caledonii) and Scandinavian colonists. Their kings ruled from the 3rd century AD until the 9th century, by which time their histories and legal rulings were written down in language that modern scholars understand. And the Pictish settlement at Ellon expanded to become the administrative and judicial centre of Buchan.

The language of the Picts, related to the Celtic British languages of the South rather than Gaelic, is thought to have been brought to the area by Irish invaders and became extinct during the middle ages. Their Ogham writing and Pictish symbols are slowly being deciphered. A Pictish Symbol Stone is built into the North wall of Ellon Parish Church, unfortunately incomplete as it had to be heavily trimmed by masons to fit the gap, but still clearly depicting part of a cross.

Under the Pictish kings, the British title of Earl was not used. The King’s overlord in a region held the title of Mormaer and was highly autonomous. The region was known as a Mormaerdom – a name which lasted until the end of the 9th century. The first Mormaer of what became Buchan was Bede: legendary; disputed; headquartered in Ellon. From this seat of local government, Bede dispensed justice during the 6th century reign of King Brude of the Northern Picts, whose royal seat was at Inverness. But all things must pass, and the timeline of the Picts disappears during the 10th century as they merge with other peoples in the kingdom then known as Alba.

St. Ninian, thought to have been a Briton who had been consecrated bishop in Rome some time in the 5th century, came as a missionary amongst the Picts and established the first Christian cell in the area. St. Ninian's Chapel and Well were by the Chapelpark Burn near Methlick. It was St. Ninian’s disciple, St. Drostan, who founded the first monastery at Deer in 520 AD, the first location associated with the 9th century Book of Deer.

This partial copy of the Gospels, including the complete Gospel according to St. John, is famous for the notes in its margins made by monks over a 300 year period, originally in the monastery, then in the newly built Deer Abbey. The Cistercian abbey at Deer was founded by Willam Cumyn (Comyn?), Great Justiciary of Scotland, in around 1218, bringing monks and an Abbot there from Kinloss. Thus, the Book of Deer, containing some of the oldest known examples of Irish Gaelic in Scotland found a new home. Liberated by antiquarians at some point, it passed through the hands of the Bishop of Ely before being donated by George I to Cambridge University Library in 1715. And there, in one of the margins, Ellon gets its first mention in written history in an entry from 1132.

Scots, Danes and Normans

Ellon and the surrounding settlements were in regular contact with Scandinavia. Sweyn Forkbeard, who ruled an empire which included most of Denmark and Norway, sent an army to show the locals who was boss. In 1012, the year before he added England to his possessions, a Scandinavian army landed at what is now Cruden Bay and was met by Malcolm II on the South side of the Water of Cruden. I won’t give away the ending, but the name Cruden possibly comes from “Croch Dain”, Gaelic for “slaughter of the Danes”. The kirk was established in the same year, and its dedication to Sweyn’s successor, Olaf II (St. Olaf), patron saint Of Norway and Denmark, shows the extent to which the Pictish and Scandinavian societies interacted before and after the battle. In fact, Buchan was temporarily under Norwegian rule by the middle of the 11th century.

By 1077, Malcolm III (Máel Coluim), son of Duncan, ruled most of what is now Scotland. He had a Saxon wife and territories in England, as a result of which he paid homage to William in accordance with Norman tradition. On Malcolm’s death, his brother, probably Donalbhain, reigned for the next 20 years. Then, David I, raised in the Norman court of Henry I, became the first king of the whole of Scotland. It was a thousand years ago, but these kings matter to Ellon because they oversaw the introduction of the Norman Feudal system, the slow replacement of Gaelic with early English, the transformation of Mormaers into Earls and the rise of the Comyns.

Enter The Comyns

The 11th and 12th centuries saw the Comyn family, originally from Normandy or Flanders, become one of the most powerful clans in Scotland and establish control of the whole of Buchan. In the 13th century, the Comyns raised the first of Ellon’s castles on what became known as the Moot Hill (or Earl’s Knowe), in an area including the current site of the New Inn. This castle began life as a timbered defensive tower in the Norman motte and bailey style, probably surrounded by a deep ditch spanned by a drawbridge. It had been one of the main seats of the Mormaers of Buchan and was where the Comyn Earls administered Buchan and dispensed justice. The site is now marked by a modern monument, a granite cylinder surrounded by seats, erected on the riverbank in 1977.

The strategic location of Ellon again enabled it to remain relevant. Regular fighting between England and Scotland was centred on the border and ravaged both Northern England and Southern Scotland. This made more distant places, like Buchan, ideal locations in which to build up support and forces. But in less than a century, the Comyn family lost its power. The details of those years, though sometimes sketchy, feature famous names and shifting allegiances. These were the Wars of Scottish Independence in which thousands of ordinary people died trying to replace one autocrat with another. This activity has been popular with the peoples of every nation for thousands of years and mankind is still at it, so we mustn’t judge.

1296 and All That

From 1296, after Wallace had been handed over to the English, John Comyn and Robert the Bruce were effectively co-leaders of the Scottish forces. They were successful in their forced partnership – but always bitter rivals.

Robert was a soldier, a skillful military leader and politically astute. The game was finally up for the Comyns when John “the Red”, 2nd Earl of Buchan and seen by many as the strongest claimant to the Scottish throne, was killed by Robert the Bruce and his followers. In 1308, probably May, his successor, also John, mustered his troops near the Moot Hill and set out for Inverurie. They were defeated at the Battle of Barra Hill. Robert had been seriously ill for much of the conflict, but the Comyns appear to have gained little advantage from this fact. Robert’s troops followed up his victory in the same year with the Harrying of Buchan, events famous for their savagery at a time when savagery was by no means unusual in war. All of the area’s fortifications were torn or burnt down, Comyn loyalists were killed, livestock and crops destroyed and much of Ellon, being the Comyn capital, was razed to the ground. In the Middle Ages, it was important to be on the winning side.

The Comyns who made it to safety in England pursued their claim to the Earldom of Buchan, becoming one of the causes of the Second War of Scottish Independence in 1332, but none of this helped the people of Ellon. In the twighlight of Robert’s kingship, the Church at Ellon and its revenues were transferred to the ownership of the Abbey at Kinloss.

Great men come and go and Robert died in 1329. The landscape is what it is, ordinary folk have lives to lead and people need to travel between Aberdeen and Buchan. The ford at Ellon was still the only place to cross the Ythan with livestock, crops, carts and non-swimmers, so the settlement slowly regenerated itself while the Comyns became a forgotten footnote in the history of the town. After the downfall of the Comyns, ownership of their lands around Ellon reverted to the crown until they were gifted to Alexander Stewart, Earl of Buchan, by Robert II. By the 15th century, the Cummings (as they had become) were just another clan.

Castles

The second (and more substantial) Ellon Castle began as a fortified house, the Fortalice of Ardgith, from the mediaeval Latin "fortalitia", meaning “fortification”. Ardgith itself appears to come from 2 gaelic words meaning “high ground” and “wind”. Isobel Moffat sold the Hill of Ardgith to Thomas Kennedy, Constable of Aberdeen, in 1413. The house, which Thomas had built, became the family seat of the Kennedys of Kermuck (or Kenmuck or Kinmuck, depending on whom you believe). In time, the ground where the Moot Hill castle once stood became a common green running from the Market Square to what is now Bridge St. The 16th century saw the first reconstruction of the castle, this time as an altogether more substantial fortress. It was built by John and Thomas Leiper, local masons who had worked on Tolquhon Castle, the House of Schivas and the Forbes Monument at Tarves Parish Church.

The castle grounds played host to the annual, hugely popular Ellon Show, run by the Ythanside Farmers’ Club and featuring livestock and equipment displays, racing, dancing, piping and ending with an evening dance.

The Castle of Waterton was a fortified tower house, the remains of which can be seen on the north bank of the Ythan. It was built around 1630 for the Forbes family. The Kennedy (Ardgith) and Forbes families clashed when Kennedy attempted to run a mill race across a road. In spite of the intervention of a clergyman, a skirmish involving 30 men resulted in some serious injuries. It took Forbes 4 months to die from his.

Old Slains Castle, built in the 14th century by the Hays, was blown up in 1594 on the orders of James VI, whom the Hays did not wish to be king because he didn’t do Christianity right. At the end of the 16th century Francis Hay, the Earl of Erroll, had a new Slains Castle built, to the North of the first.

The Manor of Eislemont, first attested in the 14th century when it passed to Francis Cheyne through his marriage to Janet Mareschal, was originally a defensive enclosure with a few farm buildings, A feud between the Cheynes and the Hays of Ardendracht, its causes lost in time, resulted in the destruction of the enclosure in 1493, in retaliation for the Cheynes’ burning of Ardendracht. In the late 15th century a new tower house was added and by 1515 Esslemont was described as a fortalice and manor. It must have been fairly swish as Mary, Queen of Scots stayed there in 1564. It was improved by the Cheynes until, in 1625, it passed to the Errol family, after which it slowly fell into disuse . War in 1646 saw Essilmounthe (as it now was) occupied alternately by Covenanters and Royalists . The estate was finally bought by Robert Gordon in 1728 but the castle was abandoned and fell into ruin once the current Esslemont House was built in 1769. This beautiful mansion house now plays host to an annual fete which celebrates its history and shares the produce of the estate

Knockhall castle, a 3 storey L shaped tower house, was built by Lord Sinclair of Newburgh in 1565. Bought by Clan Udny in 1634 it was attacked then restored, even extended, a couple of times over the next decade during the first Bishops’ War. The castle was still in use as a family home until it was gutted by fire in 1734.

Gight Castle, another L-shaped tower, was probably raised in the 16th century by George Gordon and abandoned on the death of its last inhabitant in 1791. It is famous as the ancestral home of Lord Byron, who left an epitaph for all of these ruins in his poem, Childe Harold:

“And chiefless castles breathing stern farewells

From gray but leafy walls, where Ruin greenly dwells”

James VI and Beyond

In the 17th century, the first attempts to bridge the Ythan at Ellon failed because the money could not be raised. People’s minds were clearly on higher things. The Roman Catholic church in Ellon was closed during the Reformation, but the building remained and enterprising ministers of other denominations reopened it - sometimes to Presbyterians, sometimes to Episcopalians. In 1602 the Church underwent substantial repairs after the neglect of the Reformation. These included the erection of a bell house with a public clock, the first we know of in Ellon’s history, and just in time for some more fighting. As civil war touched all parts of the British Isles, Covenanter troops found themselves quartered in Ellon whilst the Royalists were garrisoned at Fyvie. When troops were not fighting (and they were serious about fighting - over 30 died in a single encounter at Esslemont) they passed their time annoying the locals. In 1653, some of Cromwell’s troopers destroyed the clock as well as the place of repentance in the church. Absolution being more important than timeliness, the place of repentance was repaired. The clock never was.

For centuries, the Ythan had been a pearl fishery and, in 1620, the Kellie Pearl, found in the Kellie burn at Methlick, was presented to James VI. It is now part of the Scottish Crown, seen on the coffin of Queen Elizabeth II on its journey from Balmoral to Edinburgh.

The restoration to the throne of Charles II in 1660 prompted more religious conflict. The majority of Scots was Presbyterian, whereas the Church of England supported Episcopacy in Scotland. The compromise solution was the implementation of a moderate form of Presbyterianism, but Ellon (and the North East generally) supported Episcopacy and was staunchly Jacobite. In 1711, further religious conflict between the Episcopalians and Presbyterians resulted in the riot known as the Rabbling of Deer. William III made the Church of Scotland Presbyterian, effectively disestablishing the Episcopal church. Ellon took little notice, only accepting a new Presbyterian minister on the death of the old Episcopal one. A column of the Prince’s army crossed the ford en route to Culloden, taking with it a number of eager Ellon citizens. Few returned. Ellon had stood firmly by its principles again so some of the Hanoverian victors turned up and burnt down the latest Episcopal Church.

The early 18th century saw the building of the Tolbooth in the Square, replacing the Motte as the centre of administration, law and justice. It included a jail and large grain and salmon stores, because not everyone could pay rent and fines in cash. It lasted until 1842, when it was demolished and its functions centralised in Aberdeen. The only remnant of it, Baillie Gordon’s coat of arms, was taken from the original building and is now a feature of the gable wall of the building occupied by Raeburn & Christie.

Haddo House, designed by William Adam, was built for the Gordon family in 1732 to replace Kellie Castle, which had been burnt down by Covenanters. Built in the Georgian Palladian style, it is now a stately home to art and antiques collections and includes a chapel, a theatre and rehearsal rooms. It was acquired by the National Trust for Scotland in 1979. The grounds are extensive and used by cyclists, walkers, picnickers and wildlife watchers.

Finished in 1793, the new bridge finally made the ford redundant. Thus, after 2000 years, Ellon’s gift to the nation moved 60 yards upstream. Interestingly, James Robertson, the Banff mason who had finished a similar bridge for Inverurie in 1791, not only designed the Ellon bridge but had some of the temporary construction timbers floated down the Don from Inverurie, shipped north to Newburgh then up the Ythan for reuse in his new bridge. This first bridge was used until 1940, when a new, new bridge made it the Auld Brig, now a category A listed building open to pedestrians only. In 1799 most of the old Moot Hill was levelled to make way for the building of the new turnpike road between Aberdeen and Peterhead. The first public coach between the two started in 1816, stopping at the New Inn while the horses were changed and passengers did the necessary.

Ellon’s medieval church was demolished around 1776 and rebuilt nearby, reusing many of the original stones, so all that remains is the ruin of the aisle used by the Annands of Auchterellon. Since the Disruption of 1843 split the Church of Scotland, Ellon has seen a number of new churches flourish. The United Presbyterians, the Free Church of Scotland, the United Free Church and St. Andrews United Free Church all occupied buildings around the town at different times. It wasn’t until 1934 that mass was celebrated again in public in Ellon. The single room used for Roman Catholic services, restarted thanks to the tenacity of Victoria Ingrams, was finally superseded by a new church in 1992.

On the Ythan at Logie Buchan

(Chris McElvar photos)

The Industrial Age

In the 19th century, the industrial revolution arrived and, by the end of the century, Ellon, by then a centre for textile manufacturing (stockings being a speciality), added a fully equipped boot factory.

Ellon flourished. More tolls, more visitors, more markets. Gas street lighting arrived in 1827. In 1854, the castle was enhanced with the 12 ft high Deer Dykes. and, after many decades of holding secret services in temporary chapels, Ellon’s Episcopalian church was rebuilt as St. Mary on the Rock. When it opened in 1871 it was one of 5 churches in town. There were 3 taverns where people could meet to do business, drink, eat and find lodgings, 3 banks, a post office, a good selection of shops and markets in Market Square every fortnight. As well as the trades in food and manufactured goods, Ellon played host to a labour market every 6 months, in which hundreds of workers were hired to work on the surrounding farms.

The Square

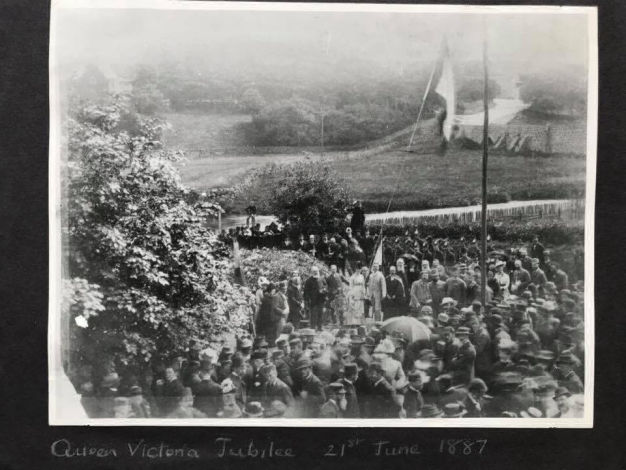

Victoria's Golden Jubilee (George Cheyne collection)

The Rise and Fall of the Railways

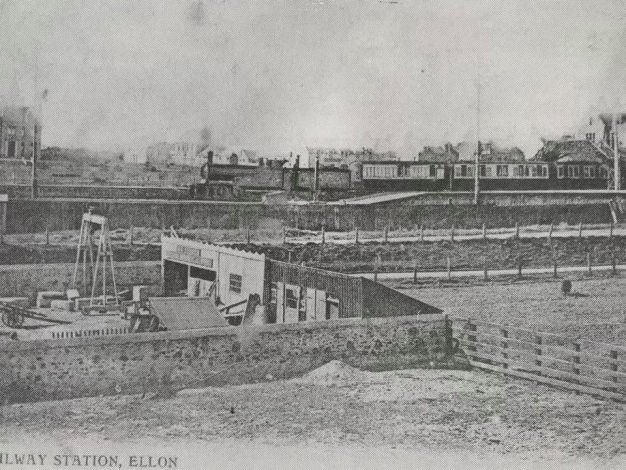

The Formartine and Buchan Railway Co., part of the Great North of Scotland Railway, had been established in 1861 to operate a new railway line. Ellon railway station and the Ythan Railway Bridge opened in July 1861, as part of a line linking Aberdeen to Peterhead and Fraserburgh via stations at Arnage, Esslemont, Auchnagatt, Maud to the North and Logierieve and Udny to the South. In 1897, the golden jubilee year, Ellon station became a junction when a new line opened between Ellon and Boddam, stopping at Auchmacoy, Pitlurg, Hatton and Cruden Bay. There was even a tourist halt at the Bullers of Buchan. In 1899, the Cruden Bay Hotel opened, connected to the station there by tramway. Yet, in less than 50 years, the lack of passengers had turned the whole line into railway offices and wagons awaiting repair. Rescue seemed to be at hand when the railways were nationalised in 1948. However, the national British Railways Board closed the branch line shortly after nationalisation, then the mainline in 1964. This same period also saw the end of the steam tugs and shallow-drafted boats which took goods upstream to Ellon from the quay at Newburgh, where clipper ships and North Sea barges loaded and offloaded. Cargoes were getting larger and efficiency was the goal, so these activities were increasingly centralised in Peterhead and Aberdeen.

1930s Ellon Station

1900s Forbes' stone yard (George Cheyne collection)

Modern Times

The 20th century saw a rapidly growing need for motorised agriculture. This led Neil Ross, who'd started a bicycle works and wireless shop (obviously!) in what became Casa Salvatore, to open his motor garage and repair shop on Bridge St., followed by the Neil Ross Tractor Works, eventually the largest in the North East and celebrated in the Frank Pottinger sculpture on Neil Ross Square. The square, only created in 1991, has since taken over as the focal point of Ellon commercial life from the original Market Square, where the war memorial now stands.

In the early years of the century, as the welfare state was finally established and consensus began to form around the creation of a National Health Service, what was left of the Moot Hill was finally flattened. Electric lights were in place in time to illuminate the young men and women waiting to sign up for war. In 1914 and 1939, the town responded as well as it had ever done to the call for volunteers to fight. There are 137 names on the War Memorial in the Square.

Newburgh’s importance to Ellon is first attested in the Book of Deer in a 1267 entry which describes it as the “port of Ellon”. In the early 1940s, the invasion threat from Germany’s Norwegian units could not be ignored so the dunes were turned into defensive dykes with the addition of pill boxes, barbed wire, landmines and anti-tank blocks. The invasion never came, but the defences were bombed several times.

While the enemy wrought destruction, Haddo House embraced creation. WWII saw it transformed into Haddo Emergency Hospital, a large maternity unit for mothers-to-be evacuated from the Central Belt. The record shows that almost 1200 babies were born here.

Memories have faded as the last eye witnesses to the Second World War have passed away. But before the sons of Ellon became names on a monument, they had fought across the continent, in the deserts of North Africa and the jungles of the Far East, and helped to liberate the concentration camps - lest we forget.

The Square in the 1920s

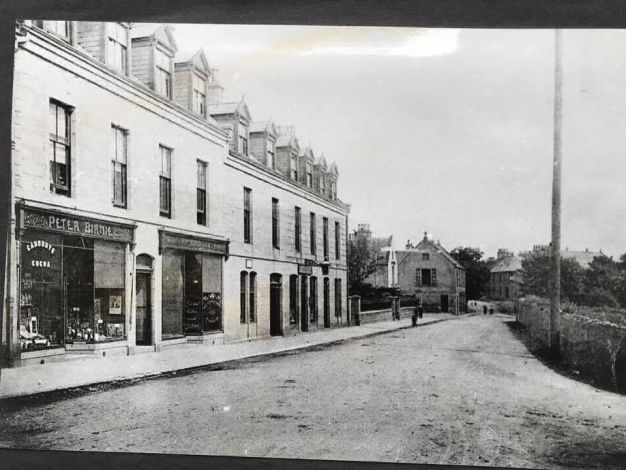

1900s Market Street (George Cheyne collection)

Brave New World

After a 50 year gestation period, the NHS was finally born and the welfare state began to grow again. In the post-war years, the demand for goods and services took off and businesses responded, transforming sole proprietors like Bain, the butcher at Tarves and Wilkie, the blacksmith at Newburgh, into multi-million pound companies.

From the 1970s onward, the location of Ellon between the two major oil industry and fisheries hubs in Northern Scotland was a double-edged sword. The fishing industry on the North East coast was greatly diminished, and many traditions lost but, thanks to the oil boom, Ellon grew. Increasingly, the people were employed elsewhere: Aberdeen; Peterhead; oil towns with an air link. And many of these workers chose to shop near their places of work. Close to half of the population is made up of commuters now. Still, there were more houses, more people and more money - Ellon had become a commuter town. Whenever downturns hit the oil industry, employment, house prices, retail spending and savings fell. In the 21st century, Ellon was still recovering from the last downturn when the Coronavirus arrived. As a result of its location so close to the Ythan, something which had served the town so well for centuries, Ellon also experienced significant flooding and property damage when the river burst its banks in 2016.

Like many small towns, Ellon is now bypassed by the main arterial route that once ran through it as the main road crosses the Ythan to the east of the town. This change was a real challenge for retailers, but it ensured that the town remained a great place for families. Small, clean and unhurried, Ellon is surrounded by National Trust and Historic Scotland properties, magnificent, unspoilt beaches, dunes and harbours, countryside trails for hikers and bikers, golfing, shooting, fishing and riding venues and an extensive artistic network. Wildlife watchers have their pick of fields, woods, estuary views, inland lochs, cliff nesting sites and numerous breeding colonies. The waters are clear, the air is fresh and the pace of life is your own.

The Ellon & District Historical Society (pictured here, en route to their AGM) published a map guiding the reader around places of interest in the town centre. You can find them HERE.

Drag & Drop Website Builder